Figure

1: The Gleaves class destroyer USS Turner

(DD-648) headed for the Brooklyn Navy Yard at Brooklyn, New York, for a

scheduled refit and repair period in April 1943. Photograph courtesy of Bill Gonyo. Click on photograph for larger

image.

Figure 2: USS Turner (DD-648) photographed from a blimp, 6 September 1943. Photograph courtesy of Fred Weiss; original print from the US National Archives. Click on photograph for larger image.

Figure

3: Photograph of USS Turner (DD-648) dated 18 January 1943,

but actually taken several months later. This image was retouched by the

wartime censor to remove radar antennas atop the ship's foremast and Mk. 37 gun

director. However, the censor did not remove the SG radar antenna on the foremast. Courtesy

Ed Zajkowski and Robert Hurst. Click on photograph for larger image.

Figure 4: Captain Frank A. Erickson, United States Coast Guard (USCG). As the Coast Guard’s first helicopter pilot, Erickson flew badly needed blood plasma from New York City to Sandy Hook, New Jersey, in a terrible snowstorm to assist the wounded survivors from USS Turner, which sank off the coast of New York on 3 January 1944. It was the first time in history a helicopter was used in a life-saving emergency. Photograph courtesy of the USCG. Click on photograph for larger image.

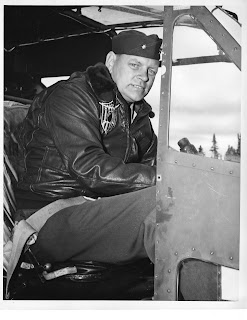

Figure 5: Then-Commander Frank Erickson, Coast Guard Helicopter Pilot No. 1, in the cockpit of a Sikorsky HNS-1 Hoverfly. Photograph courtesy of the United States Coast Guard. Click on photograph for larger image.

Figure 6: Commander Frank Erickson poses with a Sikorsky

HNS-1 Hoverfly. Photograph courtesy of the

United States Coast Guard. Click on photograph for larger image.

Named after Captain Daniel Turner (1794-1850), a naval hero from the War

of 1812, the 1,630-ton USS Turner

(DD-648) was a Gleaves class

destroyer that was built by the Federal Shipbuilding & Drydock Company at

Kearney, New Jersey, and was commissioned on 15 April 1943. The ship was

approximately 348 feet long and 36 feet wide, had a top speed of 37 knots, and

had a crew of 261 officers and men. Turner

was armed with four 5-inch guns, four 40-mm guns, five 20-mm guns, five 21-inch

torpedo tubes, three “Mousetrap” depth-charge projectors, and two depth-charge

tracks on the stern of the ship.

After completing her shakedown cruise in Casco Bay, Maine, in early June

1943, Turner steamed to New York City

to prepare for her first assignment, a three-day training cruise with the newly

commissioned aircraft carrier, USS Bunker

Hill (CV-17). After that, the destroyer embarked on her first wartime

assignment, which was to escort a convoy across the Atlantic Ocean. On 24 June

1943, Turner left Hampton Roads,

Virginia, and assisted in escorting a convoy to Casablanca, French Morocco,

arriving there on 18 July. Turner

left Casablanca on 23 July to escort another convoy back to New York City,

which arrived there on 9 August. Later that month, Turner was part of a convoy to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, making a brief

stop at Hampton Roads along the way. On the return trip back north, Turner rendezvoused with the aircraft

carrier HMS Victorious and escorted

the British ship to Norfolk, Virginia.

During the

first two weeks of September 1943, Turner

conducted anti-submarine warfare training at Casco Bay, Maine, and then

returned to New York to prepare for her second trans-Atlantic voyage. On 21

September, the destroyer headed south to Norfolk. She arrived there on 23

September and the next day headed out across the Atlantic with a new convoy.

After an eighteen-day journey, during which Turner

made one depth-charge attack on a sound contact, the destroyer arrived at

Casablanca on 12 October. Four days later, Turner

left Casablanca and headed to Gibraltar to join another convoy. She reached

Gibraltar on 17 October and after staying in port for two days joined convoy

GUS-18 for the trip back to the United States.

On the night

of 23 October 1943, while acting as an advance anti-submarine escort for the

convoy she was sailing with, Turner

located an unidentified surface contact on her radar. At approximately 1943

hours, only eleven minutes after making her initial radar contact, Turner’s lookouts made visual contact

with what appeared to be a German U-boat running along the surface roughly 500

yards away. Turner immediately turned

hard left and opened fire with her 5-inch, 40-mm, and 20-mm guns. Turner’s gunners scored one 5-inch hit

on the U-boat’s conning tower, as well as several 40-mm and 20-mm hits on other

parts of the enemy submarine. The U-boat began to dive and slipped beneath the

surface before Turner had an

opportunity to ram her. But as the U-boat dove deeper into the ocean, Turner began a depth-charge attack. Turner dropped two depth charges and

both of them appeared to hit the water just above the submerged German

submarine. As Turner kept moving over

the area where the U-boat was, she dropped another depth charge off her stern.

Soon after the three depth charges exploded, Turner’s crewmen heard a fourth explosion, the shock from which

caused the destroyer to lose power to her radar systems, her main 5-inch

battery, and her sonar equipment. It took Turner’s

crewmen roughly 15 minutes to restore full power to the ship.

Once she

re-gained full power, Turner began

searching the area for evidence to corroborate a sinking or regain contact with

the submarine. At 2017 hours, Turner

picked up another contact on her radar, this one located roughly 1,500 yards

off her port beam. Turner came left

and headed toward the contact. Not long after that, crewmen on Turner’s bridge sighted an object lying

low in the water. The crewmen on the bridge definitely identified the object as

a submarine which appeared to be sinking by the stern. Unfortunately, Turner had to break contact with the

U-boat in order to avoid a collision with another of the convoy’s escorts. By

the time Turner was able to resume

her search, the U-boat had disappeared. Turner

and the destroyer escort USS Sturtevant

(DE-239) remained in the area and conducted further searches for the submarine

or for proof of her sinking but failed in both instances. All that can be said

is that Turner probably heavily

damaged the U-boat and may have sunk her, noting it only as a “probable kill.”

On 24 October,

Turner and Sturtevant rejoined the convoy and all the ships continued their

journey without further incident. The convoy then divided itself into two

groups on 4 November. Turner took

station as one of the escorts for the group that was headed for Norfolk. Two

days later, Turner and the ships she

was escorting safely reached port. Turner

then left Norfolk to return to New York, where she arrived on 7 November.

After

remaining ten days in port, Turner

conducted anti-submarine warfare exercises at Casco Bay before returning to

Norfolk to join another trans-Atlantic convoy. Turner left Norfolk with her third and final convoy on 23 November

1943 and brought the convoy safely across the Atlantic. On 1 January 1944, near

the end of the return voyage to the United States, Turner’s convoy again split into two parts. Turner escorted the group of ships that was headed for New York

City and continued in that direction. Turner

arrived off Ambrose Light in lower New York Bay late on 2 January and anchored.

Early the

next morning on 3 January 1944, for some unknown reason Turner suffered a series of enormous internal explosions. By 0650,

the ship took on a 15-degree starboard list. Explosions (mostly in the

ammunition stowage areas) continued to tear apart the battered destroyer. Then,

at roughly 0750, a huge explosion caused the stricken warship to capsize and

sink. The tip of her bow remained above water until 0827 and then she

disappeared completely, taking with her 15 officers and 123 crewmen. After

nearby ships picked up the survivors of the sunken destroyer, the injured

crewmen were rushed to a hospital at Sandy Hook, New Jersey. But the hospital at Sandy Hook needed vital

blood plasma to treat many of Turner’s

injured crewmen, plasma it needed quickly if those sailors were to survive.

Into this

desperate situation stepped a remarkable man, Lieutenant Commander Frank A.

Erickson, United States Coast Guard (USCG). Erickson had become the first Coast

Guard helicopter pilot (Coast Guard Helicopter Pilot No. 1) in September 1943,

flying the fragile Sikorsky HNS-1 Hoverfly helicopter. Erickson was a big

believer in the future of helicopters, envisioning that one day they could be

used for rescuing people on both land and sea. Erickson was also an instructor

who trained 102 helicopter pilots and 225 mechanics, including personnel from

the US Army Air Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard, as well as the British Army,

Royal Air Force, and Royal Navy.

On 3 January

1944, Erickson received word that the hospital at Sandy Hook was in desperate

need of blood plasma to save some of the surviving crewmen from the Turner disaster. Erickson answered the

call for help by lashing two cases of blood plasma to the floats of his HNS-1

Hoverfly helicopter and flying from New York City to Sandy Hook during a

violent snowstorm that grounded all the other aircraft in the area. Erickson

successfully completed the mission and became the first helicopter pilot in the

world to fly a helicopter under such conditions. It also was the first

lifesaving flight ever performed by a helicopter. Many of those wounded sailors

owed their lives to the plasma that was brought to them by a very brave pilot

on board this new aircraft called a “helicopter.”

Erickson then

developed the idea and the techniques for the practical use of a power hoist in

helicopters. He demonstrated this near Jamaica Bay, New York, in 1944 as the

pilot of the first helicopter to pick up a man from land on 11 August 1944; the

first pick-up of a man floating in water on 14 August; and the first pick-up of

a man from a life raft on 25 September. Those demonstrations led to an official

commendation which he received in February 1945. His techniques in the use of

the hydraulic hoist and related lifesaving equipment proved of invaluable

assistance to military services and to non-military organizations. Erickson

also proved that helicopters could be used for rescues involving the lifting of

personnel, equipment, and cargo. His early demonstrations influenced the Army

to use that equipment overseas and influenced the design of numerous

helicopters in their developmental stages. He later also invented and patented

a flight stabilizer for helicopters and developed inflatable pontoons for

landing helicopters on water.

Erickson went on to

have a stellar career testing and developing the use of helicopters with the

Coast Guard and he pioneered the technique of landing helicopters on platforms

that were built on board ships. He retired from the Coast Guard as a captain on

1 July 1954. He then went on to serve as the chief test pilot for the Brantly

Helicopter Corporation while continuing to design a helicopter flight-path

stabilizer. He assisted NASA’s Gemini program in developing a hoist system to

lift an astronaut out of the water in emergency situations and consulted with

the designers of the Coast Guard’s new 210-foot Reliance class cutters in designing those vessels’ helicopter

landing pads. Captain Frank A. Erickson, a true pioneer in the history of aviation

and a man possessed with limitless vision when it came to the potential of

helicopters and their many uses, died on 17 December 1978 at the age of

seventy-one.